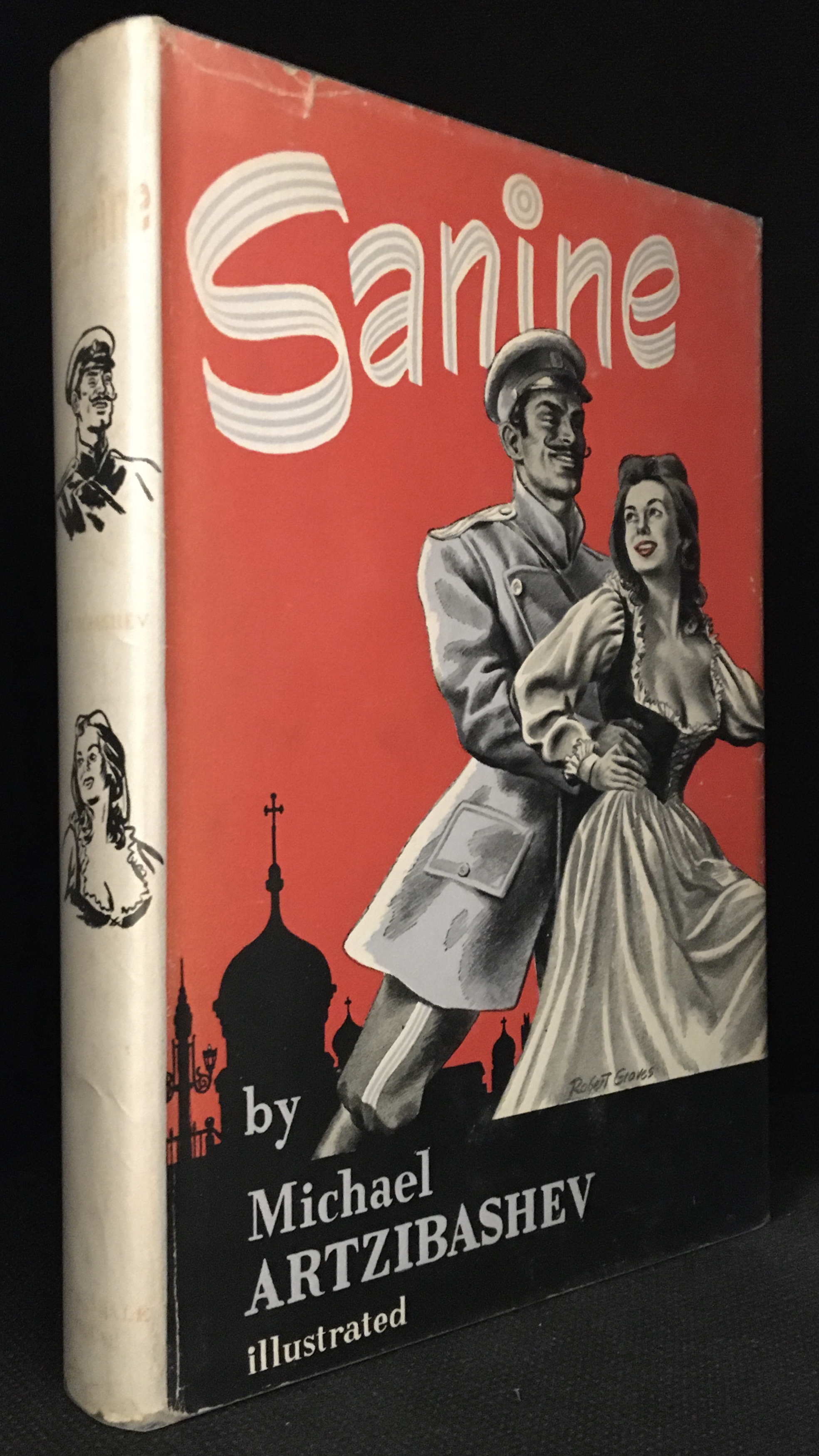

When asked, I’ve often named my favourite book of all time as a Russian novel from 1907 called Sanine by the Russian writer Artzibashev, which I have read several times since my father gave me a copy many years ago. Oddly, most Russians I’ve met have never heard of the novel or its author.

The story centres on a young man, Sanine, who returns to visit the small provincial town of his childhood after years of travelling. Importantly, the author makes clear Sanine did not spend his formative (i.e. teenage) years there, in the very first paragraph;

That important period in his life when character is influenced and formed by its first contact with the world and with men, was not spent by Vladimir Sanine at home, with his parents. There had been none to guard or guide him; and his soul developed in perfect freedom and independence, just as a tree in the field.

Right away the independently-minded Sanine finds himself at odds with those around him, starting with his family who to him seem more conformist and small-minded than ever. When his mother asks how he has spent his many years away, he replies:

“I ate, and drank, and slept; and sometimes I worked; and sometimes I did nothing!”

His mother’s reaction is one of frustration and disappointment:

It pained her to think that her son did not occupy the position to which, socially, he was entitled. She began by telling him that things could not go on like this, and that he must be more sensible in future.

He is appalled to see the self-destructive behaviours around him – his beautiful young sister Lida in a hopeless affair with Sarudine, a handsome cavalry officer, master-seducer and all-round cad who sees her as little more than a fresh notch on his bedpost. Then we have Sanine’s ‘nice guy’ friend Novikoff who in turn is in love with Lida, bombarding her with futile romantic gestures and proclamations, yet utterly failing to generate the raw sexual attraction of his more cynical and skilful rival. Lida finally gives in to Sarudine’s charms, loses her innocence to him and falls pregnant, only to be immediately abandoned by the officer.

Sanine’s very essence is one of non-conformity, going wherever his instincts and desires lead, largely unaffected by the reactions and opinions of others. In a sense he has risen above the petty concerns, obsessions and relentless neuroses of those around him. Indeed in Gilbert Cannan’s preface to the book, Sanine is described as a man who has ‘escaped the tyranny of society’. His favourite pastimes are hanging out drinking and philosophising with his like-minded friend Ivanoff, mingling with peasants, enjoying nature and seducing country girls, including various peasant girls and family friend Sina Karsavina. He follows his passions without apology, answering to nobody.

And yet he does have moral standards – it’s just that they are his own. He calmly tells Sarudine exactly what he thinks of him in light of his dishonourable conduct towards his sister. Sarudine later formally challenges him to a duel via his messengers. Sanine declines the invitation but, when Sarudine turns up in person, punches him in the face with such force that his good looks are ruined.

Lida and Sina are critical of Sanine for turning down the duel, with the implication that he is cowardly. Sanine is depressed by this.

Human stupidity and malice surrounded him on all sides. To find such qualities alike in bad folk and good folk, in handsome people as in ugly, proved utterly disheartening.

As far as Sanine is concerned, he dealt with the situation in the best way possible. He responded to Sarudine’s challenge. He just did so on his own terms, not Sarudine’s. By using non-lethal force he has avoided the pointless death of either man. He cannot understand why so many around him think otherwise.

There are other characters who rub up against Sanine and his worldview; Yuri, the hot-headed student and would-be revolutionary who takes himself so seriously it ultimately costs him not only his peace of mind but his life. Soloveitchik, the forever anxious, spiritually troubled Jew who, in another dark turn, Sanine persuades to end his own troubles. Indeed, this somewhat alternative view regarding the sanctity of human life, against the prevailing Christian values, also crops up when Sanine suggests his sister get an abortion.

Despite the various apparent contradictions, Sanine’s actions are all consistent with his philosophy. Death resulting from a duel, either Sarudine’s or his own, would be a stupid and pointless waste. But Soloveitchik really seems too delicate for life, a temperament unfit for this world, condemned to eternal fearfulness and sadness and apparently unable to change. Sanine simply proposes a way out, reasoning that death is preferable to such an existence. Lida on the other hand has her whole life ahead of her, hence suicide would be a tragic and absurd decision, from which Sanine successfully dissuades her. Instead, getting a secret abortion would be the logical and astute move as it would allow her to start life afresh, just as if her dalliance with Sarudine never happened, with no shame or burden other than any she might carry in her mind.

Sanine stands alone against the mores of the society he has chosen to revisit. Instead of taking up an occupation and planting roots he does as he pleases, living moment to moment. Rather than marry or start a family, he seduces country virgins for sport (some might suggest this makes him no better than Sarudine – the counterargument being that whereas Sarudine makes false promises of commitment to get what he wants, Sanine is unfailingly honest. He deceives no-one).

Although affected by what surrounds him, at his core he is unshakeable, an individual of considerable mental and physical strength and resilience. Like his friend Ivanoff, with whom he loves to put the world to rights over a beer, he refuses to take anything too seriously, going through life with a carefree levity. What’s the point in worrying or being sad, he would say. Life is to be lived, the moment is to be enjoyed. If you could get out of your head for just a moment, you’d see the beauty and wonder that is all around us.

“Men always build up a Wall of China between themselves and happiness”, says Sanine in one memorable quote.

I was gripped by this novel when I first read it 20 odd years ago, and I’ve read it many times since. Friends to whom I recommended it seemed to feel the same. One even coined a saying for challenging situations – “What would Sanine do?” That the book made such an impression isn’t surprising. Sanine as an archetype has great appeal, especially for younger readers. Like other writers including Artzibashev’s predecessor Lermontov, author of Hero of Our Time (a Russian novel resembling Sanine in many ways), Norwegian author Knut Hamsun and many more, Artzibashev has created an appealing protagonist in the individualist antihero. Sanine feels immediate and present, and in translation is highly readable, despite being over 100 years old.

Of course this type of character has long held popular appeal. Sanine gets a mention in Colin Wilson’s book The Outsider, an analysis of the antihero / outsider archetype in literature through the ages. Few things resonate with young men quite like the rebel going his own way, breaking free from the expectations and constraints of society, taking what he wants along the way, not least the maidenheads of young women.

Although I still think the novel is a masterpiece, my feelings about the protagonist and his philosophy have shifted a little. Whilst I have no doubt changed and hopefully matured over the last two decades, society – and by society I mean the Western world – may have changed even more profoundly.

If Sanine is ‘a man who has escaped the tyranny of society’, considering such a character over a century later obviously requires re-examining what ‘society’ is today. This is all with the obvious caveat that this is a novel set in a small town in provincial Russia, at the start of the 20th century during the final years of the Romanovs. Revolution was around the corner and society was indeed upended on a vast scale as imperial Russia gave way to 70 years of communist rule.

All that said and without going into subjects well beyond the ambition of this post, I simply want to imagine who Sanine would be today, in the modern Western world – which I’d argue to some extent includes Russia since the USSR’s collapse and subsequent 3 decades of Western influence. Sanine was at odds with the prevailing orthodoxy of his time, which was built around things we’ve already mentioned – religion, marriage, family, career, obtaining and maintaining social status, as well as adherence to the customs and codes of the time, i.e. duels fought by the nobility.

As a thought experiment, let’s place the Sanine of 1907 provincial Russia directly into the modern world. Do we still find him at odds with ‘society’? He tells his sister Lida an abortion is the best option for her. This was a huge taboo then. Though admittedly still a contentious issue, in the secularised West today, being ‘pro-life’ often seems the more controversial opinion. In any Western European city at least, Lida would be unlikely to face social condemnation for such a decision, and she’d certainly have the support of the state.

What about Sanine’s unapologetic individualism and pursuit of simple pleasures? Right wing / reactionary thinkers would argue that this is exactly why our civilisation is falling apart. What’s the end result of a society filled with Sanines? Falling birthrates, less marriage, fragmented families and communities – a hedonistic world where everyone is simply out to get their rocks off with no thought for the future. In a word, collapse. Weimar Germany perhaps. Is selfish pursuit of pleasure a rebellious or dissident position today? Hardly. You could make a solid argument that mainstream Western media encourages these attitudes.

How about the somewhat shocking scene where Sanine convinces Soloveitchik he may as well end his life, if he’s so unhappy? Unbelievable as it might seem, the Canadian authorities today might not only approve Soloveitchik’s decision, but do the work for him.

So is Sanine ruined for me? Far from it. As a character he isn’t defined by his surroundings. I always understood Sanine as the manifestation of a strong spirit who refuses to bend to the whims of society (AKA The Current Thing), acting in loyal accordance to his own moral framework, no matter if it clashes with the widely accepted / dictated moral framework of the time. I’m fairly sure he would abstain from taking a unproven ‘vaccine’, especially in the face of mandates or heavy coercion from the state aided by the mainstream media, quietly and without fanfare resisting all pressure, whether social – i.e. being labelled a ‘granny killer’ – or institutional, i.e. being threatened with restriction of his personal freedoms. Being a free spirit, he’d find a way around that too if needed.

It isn’t hard to imagine Sanine’s disapproving mother berating him for endangering those around him by not wearing a mask at all times. Instead of scorning him for not partaking in a lethal duel, those close to him might instead shame him for not getting ‘the jab’, yet Sanine’s logic and reasoning remain exactly the same. We return again to Sanine’s glum thoughts about those around him.

Being the rebellious spirit he is, he might choose to defy the prevailing ‘hookup culture’, not to mention the depopulationist agenda, and get married and start a family. The bigger the better.

I’ve had something like writer’s block in recent years, putting writing aside to focus on other things. Firstly I believe a writer shouldn’t really bother writing without something important to say. Secondly, I feel what I do have to say might, for now, be better left unsaid. It’s hard to keep up with our rapid descent into what the dissident right have nicknamed ‘Clownworld’. Third, as an afterthought, I’ve never liked the idea of being overtly political in my creative output. The politics of the day come and go, but certain ideas remain timeless.

Clownworld, characterised by domination of the media and seemingly every Western cultural institution by the far left, abetted if not spearheaded by globalist-technocratic leadership, seems to originate from the United States of America. The UK, the rest of the ‘Anglosphere’ – that is to say the English speaking world including Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as most of Western Europe, tend to be culturally downstream from America. Whatever happens there usually reaches us before long. Once it was the Hollywood movie industry, Coca-Cola and Levis Jeans. Today it’s the domination of big pharma, ‘gender theory’ and all its offshoots, such as gender ‘pronouns’ (now seemingly ubiquitous in Western academic and corporate culture) ‘critical race theory’ and all its offshoots, such as the conception of ‘whiteness’ as some sort of pathology, ‘body positivity’ (the endorsement of obesity) and so on ad nauseam. It’s as if the West, in other words the European-founded world sits mouth agape, ingesting the non-stop stream of cultural sewage coming from the USA, and the stream has only intensified with time.

There is a compelling argument that many of the ideas bubbling under the surface in Sanine’s world, right on the cusp of erupting into full-blown revolution in Russia, are in fact the direct origin of the current dominant Western culture via the Frankfurt School and the left’s ‘long march through the institutions’, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

Today we find ourselves in a zeitgeist well advanced beyond the non-conformism of the 1960s ‘hippy era’. We’re told small families or better still no children at all is a good thing, because of climate change you see, not to mention the fact that absolutely everything is racist – but only in the context of the current ‘redefinition’ of racism. Freedom? We’ve never been freer – small children can even choose what gender they want to be. So much for God’s design!

The idea of a novel about a modern technocratic dystopia, something like a current version of 1984, Brave New World or Zamiatin’s We hardly seems original now. I genuinely hope that much of what I’ve written in the couple of paragraphs above will date poorly. And yet it does seem that just when things can’t get any more ridiculous, they do. Still, I can’t help but suspect that not too far in the future, the period of time when we were told women are men and men are women (and indeed can give birth and menstruate) will be remembered as a bizarre footnote in history. We can only hope.

By definition, the antihero transcends the zeitgeist. When the majority tolerate or even defend what they know is wrong, either from a desire to virtue-signal or some other type of moral cowardice, then by default opposing tyranny falls to those unafraid to stand against the tide. They might not be paragons of virtue or morality themselves – but betraying their own principles, at least, is alien to them. Far from being an anachronism shaped only by the environment and era into which he was born, for me at least, Sanine holds up as an antihero for our times.